⦁ China’s Strategy in Afghanistan: Moving Beyond Classical Great Power Foreign Policy Models

⦁ China’s Tools in Afghanistan: Selective, Limited, and Security-Oriented Measures

Introduction

Afghanistan, due to chronic insecurity, weak statehood, and political instability, has become an influential focal point in the region’s security and geopolitical equations. China, which considers peripheral stability as a prerequisite for domestic development and the success of its regional initiatives, views Afghanistan as a high-risk strategic challenge. However, this importance does not translate into a desire for direct intervention or the assumption of a hegemonic role. China’s strategy is founded on preventing the spillover of regional instability, a calculated increase in diplomatic engagement, and avoiding entrapment in the “Afghan trap.”

The historical experience of relations between the two countries, from the 1950s to the present, has led to the formation of a durable pattern based on risk management, limited assistance, and avoidance of heavy security commitments—a pattern that continued, in an adjusted form, in China’s engagement with the Taliban in the 1990s and after 2021.

This report, focusing on the historical trajectory of China–Afghanistan relations, examines the structural drivers, strategic logic, and policy instruments shaping China’s approach toward Afghanistan.

The Logic of China’s Strategic Behavior in Afghanistan

History and Configuration of China–Afghanistan Relations

China–Afghanistan relations took shape after 1949 within a cautious, low-cost, and non-interventionist framework, and Afghanistan from the outset occupied a marginal position in Beijing’s foreign policy priorities. During the early decades of the Cold War, China’s policy was subordinate to its relationship with the Soviet Union, and the assistance provided to Kabul remained largely limited, symbolic, and humanitarian. Afghanistan’s caution in maintaining neutrality and the Soviet Union’s structural dominance in economic and security spheres prevented the expansion of China’s independent influence. Following the Sino-Soviet split in the early 1960s, Beijing attempted to play a more active role in Afghanistan, but these efforts also yielded no significant strategic gains due to the continued dominance of the Soviet Union.

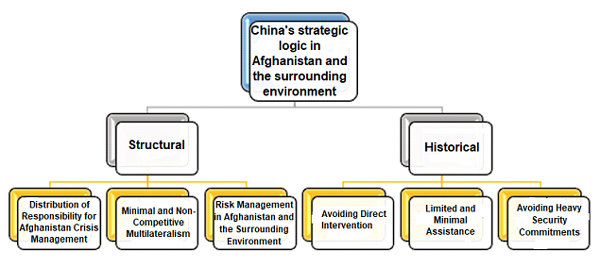

The outcome of this experience was the consolidation, by 1966, of a stable pattern that viewed Afghanistan as a high-cost environment with limited strategic returns, emphasizing avoidance of direct intervention, limited assistance, and abstention from heavy security commitments. This “historical strategic memory” was later institutionalized within China’s broader peripheral diplomacy which based on minimal risk management, multilateralism, and distancing from costly security responsibilities.

This logic also persisted in China’s approach toward the Taliban: from non-recognition of the Taliban in the 1990s while maintaining limited contacts, to political support for the republic government after 2001 without military intervention, and subsequently a gradual shift toward keeping all options open as U.S. presence declined.

After the fall of Kabul in 2021, China, consistent with this pattern, did not rush to recognize the Taliban. Instead, it opted for gradual and functional engagement, maintaining its embassy and demanding security guarantees—particularly regarding Xinjiang. Overall, the historical trajectory of relations shows that China’s policy toward Afghanistan has consistently been based on risk control and avoidance of the “Afghan trap,” defining Afghanistan not as a problem to be solved, but as a “variable to be managed.”

Structural Pressures Shaping China’s Behavior in Afghanistan

China’s behavior toward Afghanistan, beyond its historical logic, is influenced by a set of structural pressures that compulsorily define the scope and direction of Beijing’s actions. The first factor is the withdrawal of the United States and NATO, which, instead of creating stability, left behind a security vacuum and a fragile order. This situation simultaneously pushed China toward greater engagement to prevent collapse while forcing it to seriously avoid direct intervention. As a result, since 2013, China’s engagement has primarily proceeded through diplomacy, limited economic assistance, and multilateral mechanisms.

The second structural pressure is the direct linkage between developments in Afghanistan and China’s peripheral and domestic security. Instability in Afghanistan can threaten Xinjiang, Central Asia, and China’s regional projects. Therefore, China considers Afghanistan as a part of its immediate security environment and views its engagement as preventive in nature, aimed at stopping the country from becoming a hub of chronic insecurity.

The third factor is the intensification of great power competition and the diversification of regional actors in Afghanistan. This has complicated China’s policy space and pushed Beijing toward an approach that neither leads to direct confrontation with other powers nor to withdrawal that would exacerbate instability. The result is a tendency toward minimal, non-competitive multilateralism.

The fourth driver is the role of regional institutions and mechanisms through which China seeks to institutionalize the management of the Afghan crisis, distribute costs and risks, and avoid the concentration of responsibility on itself. Examples such as the Istanbul Process, the Beijing Declaration, and efforts to link Afghanistan with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) illustrate this approach. Overall, China’s policy toward Afghanistan is less a product of voluntary ambition than a structural reaction to external conditions, positioning China as a cautious actor managing peripheral risks rather than a hegemonic intervener.

China’s Strategy in Afghanistan: Moving Beyond Classical Great Power Foreign Policy Models

China’s strategy in Afghanistan goes beyond classical great power foreign policy models—such as security intervention, state-building, or reconstruction leadership—and is based on a cautious logic of “peripheral risk management.” The primary objective of this strategy is not to resolve the Afghan problem, but to contain the spillover effects of its instability on China’s surrounding security environment—an understanding rooted in Beijing’s historical experience of Afghanistan as a costly arena for external powers.

Within this framework, China views reconstruction not as an ambitious project, but as a limited diplomatic tool to create a minimum level of stability. By focusing on targeted, temporary, and low-cost assistance, it avoids extensive and high-risk commitments. At the same time, the principle of non-interference in China’s policy has been redefined and replaced by “responsible support,” meaning that while Beijing engages diplomatically and regionally, it refrains from direct involvement, military intervention, or assuming the role of a Western security substitute. Emphasis on Afghan ownership, by assigning responsibility for governance and stability to domestic actors, both strengthens the legitimacy of China’s non-intervention and serves as a mechanism for cost reduction and responsibility distancing — rather than reflecting its optimism about Afghanistan’s internal capacities.

Ultimately, the conscious avoidance of a hegemonic role constitutes the core of this strategy—an approach that, in light of the failures of previous powers in the “Afghan trap,” is based on limited presence, multilateralization of responsibilities, and avoidance of direct geopolitical competition. Overall, China’s strategy in Afghanistan represents a “deliberate design for controlling peripheral risks,” aimed at containing the effects of Afghanistan’s instability on China’s security, rather than rebuilding Afghanistan as an ambitious project of a great power.

China’s Tools in Afghanistan: Selective, Limited, and Security-Oriented Measures

China’s policies and instruments in Afghanistan must be understood within the framework of the practical implementation of its “peripheral risk management” strategy—a strategy grounded not in direct intervention or extensive commitments, but in selective, limited, and primarily security-oriented actions. An examination of China’s behavior over the past two decades, particularly after the withdrawal of the United States and NATO, shows that Beijing has employed a set of calibrated tools whose principal aim is not the fundamental resolution of Afghanistan’s crisis, but rather the prevention of the country’s descent into an uncontrollable source of insecurity for China’s surrounding environment. Within this framework, China’s first instrument is economy, but not in the classical sense. China does not regard Afghanistan as either a strategic economic opportunity or a sphere for expanding structural influence, and it has consciously refrained from systematically integrating it into major Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects.

Beijing’s economic interventions have largely been confined to humanitarian aid, small-scale infrastructure projects, limited workforce training, and symbolic reconstruction efforts—measures designed to preserve a minimum level of livelihood stability and prevent the total collapse of social order.

Even the notable increase in bilateral trade in recent years can be interpreted within this controlled framework, without the assumption of long-term commitments. From China’s perspective, the economy in Afghanistan functions less as a development instrument than as a preventive tool for containing peripheral insecurity, and its limitation reflects a conscious strategic decision to control costs and risks.

Alongside economic instruments, multilateral diplomacy occupies a central position in China’s policy. Beijing has sought to transform Afghanistan from a bilateral dossier into a regional issue so that responsibility for crisis management is distributed among multiple actors and pressure and costs are not concentrated on China alone. China’s active yet non-leadership-oriented participation in mechanisms such as the SCO, the Istanbul Process, and various regional dialogue formats demonstrates its preference for a “collective management without hegemony.” In addition to its practical function, this multilateral diplomacy plays a normative role, providing a platform for the reproduction of principles such as respect for sovereignty, Afghan-led processes, and opposition to military intervention—principles consistent with China’s logic of modified non-interference and reinforcing the legitimacy of Beijing’s cautious behavior.

China’s third instrument is limited and conditional mediation. Contrary to some interpretations, China has little interest in assuming the role of guarantor of political agreements or custodian of Afghanistan’s political order; and it prefers to remain a facilitator. Hosting talks, encouraging intra-Afghan contacts, and coordinating regional perspectives—without accepting direct responsibility for negotiation outcomes—constitute the prevailing pattern of China’s mediation. This approach aligns fully with Beijing’s strategic logic, since assuming a guarantor role would entail entering a costly cycle of commitment, intervention, and possible failure—a cycle China deliberately avoids. From Beijing’s viewpoint, reducing violence, preventing crisis escalation, and containing regional spillover effects are realistic and manageable objectives, whereas state-building or the full stabilization of Afghanistan’s political order are assessed as beyond China’s capacity and interests.

China’s fourth important instrument is indirect security cooperation, which has gained greater significance in recent years. China has resolutely avoided direct military intervention in Afghanistan and, even at the height of insecurity, did not join international military missions. Instead, its security cooperation has proceeded through intelligence sharing, limited training, regional counterterrorism coordination, and strengthening the security capacities of neighboring states. The principal focus of these measures is not controlling Afghanistan’s internal security, but preventing threats from spreading to Xinjiang and Central Asia. In this framework, Afghanistan’s security is not an independent objective for China, but an intermediary variable in securing its own periphery.

Overall, China’s tools and policies in Afghanistan are not the product of ad hoc or reactive responses, but part of a coherent and conscious operational pattern for managing peripheral risks.

Limited economics as a preventive instrument, multilateralism for cost distribution, mediation without commitment, and indirect security cooperation all reflect a clear strategic choice: presence without assumption of control, influence without hegemony, and participation without becoming ensnared in the Afghan trap. From this perspective, China is not seeking to resolve a chronic crisis in Afghanistan, but rather to control its consequences for the broader strategy of its peripheral diplomacy.

Lessons from China’s Strategy in Afghanistan

1. China’s policy in Afghanistan shows that Beijing is neither a comprehensive reconstruction partner nor a security guarantor. Expecting China to assume the burden of stabilization is consistent neither with its interests nor with its operational pattern. Effective engagement with China requires defining limited, low-cost initiatives aligned with the logic of risk management.

2. The Afghan experience underscores that China is willing to participate actively only within multilateral and distributed frameworks. The more multilateral the mechanisms and the more dispersed the responsibilities, the greater the likelihood of sustained Chinese participation.

3. China’s policy in Afghanistan demonstrates that the withdrawal of a dominant power does not necessarily lead to the hegemonic entry of another. In this case, China has shown that a relative power vacuum can be managed without being filled—an approach that may be replicated in other peripheral regions of the global order.

4.China’s “new peripheral diplomacy” is less a blueprint for order-building than a strategy of risk control in an era of global order transition. By combining limited presence, indirect tools, and leaderless multilateralism, China has sought to balance the imperatives of peripheral security with the avoidance of strategic erosion. This logic not only explains China’s behavior in Afghanistan but also provides a framework for understanding its role in other chronic peripheral crises.

5. The higher the uncertainty and cost of direct intervention, the more likely China is to resort to indirect, multilateral, and low-commitment mechanisms.

Conclusion

China views its surrounding environment as the front line of national security and sustainable development, and regards the stability of this environment as a precondition for continued domestic growth and resilience amid pressures arising from a transitioning global order. Within this framework, Afghanistan, in the logic of Chinese foreign policy, is not a theater for influence, state-building, or hegemonic competition, but an example of a high-risk peripheral crisis whose consequences must be contained.

China’s peripheral diplomacy toward Afghanistan rests on three core logics: prioritizing the preservation of minimal stability over direct intervention; active multilateralization without assuming hegemonic leadership; and a conscious avoidance of turning peripheral crises into long-term strategic liabilities.

Accordingly, China neither seeks to redesign Afghanistan’s internal order nor adopts a passive approach; rather, it strives to maintain a controllable level of stability by preventing worst-case scenarios—including total collapse, the expansion of transnational terrorism, and the spread of instability. This approach represents a middle path between hegemonic intervention and strategic passivity, formulated based on the principle of “risk management rather than crisis resolution.” At the strategic level, this logic is reflected in policies such as limited reconstruction, non-interference combined with responsible support, Afghan-centered governance, and avoidance of a dominant role.

At the operational level, the linkage among limited economics, active multilateralism, mediation without guarantees, and indirect security cooperation shows that China seeks to “maximize influence” while “minimizing commitments.” In sum, China’s primary objective in Afghanistan is not to resolve a chronic crisis, but to contain the consequences of its instability for China’s peripheral security and the broader strategy of its peripheral diplomacy.

QR code

QR code