Publish Date

Sunday 23 November 2025 - 08:03

recommended

1

Afghanistan at the crossroads of South Asia and Eurasia

The Possible Transition of Afghanistan from the South Asian Order to the Eurasian One

Part of Afghanistan’s challenges stem from the country’s deep dependence on the South Asian order that has taken shape over the past decades. The ongoing rivalry between India and Pakistan has imposed heavy costs on Afghanistan, and one of the reasons for the collapse of the Afghan republican system was the competition between these two countries within Afghanistan.

By: Javid Hosseini

8 Minutes Reading

8 Minutes Reading

Introduction

According to academic theories, four regional orders surround Afghanistan: the Middle East order, the South Asian order, the East Asian order, and the Eurasian order. Put simply, a “regional order” is defined as a set of political, economic, and security linkages that encompass the countries within a region. Traditionally, Afghanistan has belonged to the South Asian order whose centers are India and Pakistan—two states locked in an unending hostility. Part of Afghanistan’s crisis has been the result of the rivalry between these two states on Afghan soil, and thus Afghanistan is, in a sense, considered a victim of the South Asian region.

Since the republican era, an idea emerged advocating Afghanistan’s distancing from the South Asian order and joining the Eurasian order. However, multiple factors—including the prominent role of the United States in Afghan politics, Afghanistan’s strong dependence on India, and the ongoing war—prevented the implementation of this idea. Considering that a major part of the Taliban government’s strategic foreign policy follows the previous political system, this strategy may now be on the Taliban’s agenda. There are signs supporting this geopolitical shift which, given their significant regional implications, warrant close attention.

Assessment of the Transition; Based on Four Indicators

The hypothesis of Afghanistan’s transition from the South Asian to the Eurasian order can be tested using four indicators:

1. A shift in patterns of recognition and official diplomacy;

2. A shift in economic actors and dominant investments;

3. Transit-infrastructural agreements and projects that redefine geographic linkages; and

4. The security balance.

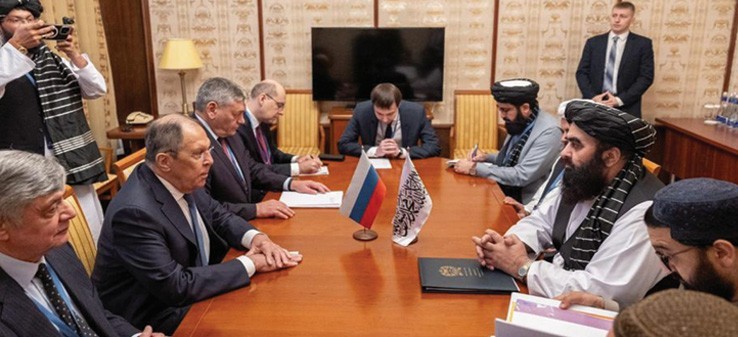

Using these indicators, certain behaviors from both sides (Afghanistan and the Eurasian region) can be analyzed as potential signs of such a transition. Although many regional countries have opened channels of engagement with the Taliban government, the engagement of Eurasian states—particularly the four Central Asian countries—goes far beyond that of other states. Russia’s move to recognize the Taliban government and its official invitation to a Taliban representative to the Moscow Format meeting are notable signs in this regard.

The volume of visits by officials from countries in this region to Afghanistan, and their invitations to Taliban officials, is significantly higher compared to other regions. These developments support the first indicator. The sign supporting the second indicator include the emergence of Eurasian countries as new economic actors in Afghanistan. Maybe it can be argued that in the absence of stronger players, Eurasian states have become more visible in Afghanistan. However, under equal conditions, Central Asian states (among various regional countries, including China) have assumed a distinctive role in economic and investment activities.

Perhaps the clearest sign relates to the third indicator: transit-infrastructural agreements and projects that redefine geographic connectivity. Despite certain risks in Afghanistan, Central Asian states—supported by Russia—have taken the lead in transit agreements and projects through Afghanistan. For example, Turkmenistan has constructed a 16-kilometer segment of the TAPI pipeline at its own expense inside Afghan territory, while Uzbekistan has demonstrated firm resolve to construct the Trans-Afghan railway. Many additional examples support this indicator.

Although evidence can be found for the first three indicators, there is still no documentation for the fourth indicator—the security balance—which is extremely important. This indicator will only be verifiable once Afghanistan joins one of the security alliances of the region. Although significant inherent and political contradictions exist between Afghanistan and Eurasian countries, especially under Taliban rule, the Eurasian order has various motivations to incorporate Afghanistan into its system.

The most important motivations stem from Afghanistan’s geopolitical, geostrategic, and geoeconomic position. Eurasian countries—particularly Russia, as the region’s leading pole—would welcome Afghanistan’s alignment with their order. They hope that such a development would not only mitigate the security threat posed by Afghanistan in terms of extremism but also prevent other powers from using Afghanistan as an arena for another Great Game. The economic and transit opportunities available to these countries through Afghan geography further encourage them to accept Afghanistan into their system. Although the ideological domestic policies of the Taliban—such as the ban on girls’ education—are criticized by these states, the authoritarian and centralized nature of the Taliban government is in many ways similar to the systems governing most countries in the region.

Potential Implications

Of course, it is still too early to speak with certainty about this transition and only certain indicators support this hypothesis. However, since this move will be strategic, it will yield geopolitical and geoeconomic consequences for neighboring regions.

Pakistan, as a member of the South Asian order, is concerned about Afghanistan’s rapprochement with Eurasia; for if this transition materializes, Pakistan’s long-held ambitions—such as its “strategic depth” policy—will collapse. Moreover, if Afghanistan disengages from the South Asian order and joins Eurasia, the new geopolitical and geoeconomic shift will benefit India. For this reason, Pakistan will attempt to prevent such a development. It may even be argued that one of the fundamental factors behind the developments of the past few months between Afghanistan and Pakistan—which resulted in military clashes—was Pakistan’s concern over this shift.

In contrast to Pakistan, India will strongly support this Afghan move because it will weaken Afghanistan’s ties with Pakistan. Should this transition become definitive, Pakistan may resort to costly measures to halt it.

If Afghanistan’s transition from the South Asian to the Eurasian order is realized, certain geoeconomic changes must also be considered. Under such circumstances, Afghanistan will seek to reduce its dependence on Pakistan and establish alternative routes. In this scenario, the port of Chabahar will have a strong chance to facilitate access for Eurasian states and Afghanistan to open waters. Likewise, the eastern branch of the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) —with India’s support—will flourish. It may also be said that the Trans-Afghan Railway project proposed by Kabul through the Kandahar Corridor aligns with this vision; because the railway through the Kabul Corridor leads toward Pakistan, whereas the Kandahar Corridor could potentially connect to Iran’s rail network and the port of Chabahar.

Conclusion

Part of Afghanistan’s challenges stem from its heavy dependence on the South Asian order, which has taken shape over the past decades. The ongoing rivalry between India and Pakistan has imposed heavy costs on Afghanistan, and one of the reasons for the collapse of the republican system was the competition between these two countries inside Afghanistan. To distance itself from this costly order, Afghanistan has the option of connecting to Eurasia —but it is a costly and time-consuming transition. Although certain indicators support this shift, they are not yet complete. - Given the profound consequences of this potential transition, greater attention is necessary. To this end, it is recommended that current trends be closely monitored:

- The visits of Afghan and Eurasian officials and the content of their discussions, including between trade delegations;

- The volume of Eurasian investment in Afghanistan compared to that of other countries;

- Progress in rail, road, and energy transit routes through northern Afghanistan;

- Security negotiations between the Taliban government and Eurasian states, particularly Russia;

- Moscow’s efforts to secure defense and military agreements with Kabul;

- Formal recognition of the Taliban government by Russia and Central Asian states.

Javid Hosseini; Researcher in Afghanistan Affairs

According to academic theories, four regional orders surround Afghanistan: the Middle East order, the South Asian order, the East Asian order, and the Eurasian order. Put simply, a “regional order” is defined as a set of political, economic, and security linkages that encompass the countries within a region. Traditionally, Afghanistan has belonged to the South Asian order whose centers are India and Pakistan—two states locked in an unending hostility. Part of Afghanistan’s crisis has been the result of the rivalry between these two states on Afghan soil, and thus Afghanistan is, in a sense, considered a victim of the South Asian region.

Since the republican era, an idea emerged advocating Afghanistan’s distancing from the South Asian order and joining the Eurasian order. However, multiple factors—including the prominent role of the United States in Afghan politics, Afghanistan’s strong dependence on India, and the ongoing war—prevented the implementation of this idea. Considering that a major part of the Taliban government’s strategic foreign policy follows the previous political system, this strategy may now be on the Taliban’s agenda. There are signs supporting this geopolitical shift which, given their significant regional implications, warrant close attention.

Assessment of the Transition; Based on Four Indicators

The hypothesis of Afghanistan’s transition from the South Asian to the Eurasian order can be tested using four indicators:

1. A shift in patterns of recognition and official diplomacy;

2. A shift in economic actors and dominant investments;

3. Transit-infrastructural agreements and projects that redefine geographic linkages; and

4. The security balance.

Using these indicators, certain behaviors from both sides (Afghanistan and the Eurasian region) can be analyzed as potential signs of such a transition. Although many regional countries have opened channels of engagement with the Taliban government, the engagement of Eurasian states—particularly the four Central Asian countries—goes far beyond that of other states. Russia’s move to recognize the Taliban government and its official invitation to a Taliban representative to the Moscow Format meeting are notable signs in this regard.

The volume of visits by officials from countries in this region to Afghanistan, and their invitations to Taliban officials, is significantly higher compared to other regions. These developments support the first indicator. The sign supporting the second indicator include the emergence of Eurasian countries as new economic actors in Afghanistan. Maybe it can be argued that in the absence of stronger players, Eurasian states have become more visible in Afghanistan. However, under equal conditions, Central Asian states (among various regional countries, including China) have assumed a distinctive role in economic and investment activities.

Perhaps the clearest sign relates to the third indicator: transit-infrastructural agreements and projects that redefine geographic connectivity. Despite certain risks in Afghanistan, Central Asian states—supported by Russia—have taken the lead in transit agreements and projects through Afghanistan. For example, Turkmenistan has constructed a 16-kilometer segment of the TAPI pipeline at its own expense inside Afghan territory, while Uzbekistan has demonstrated firm resolve to construct the Trans-Afghan railway. Many additional examples support this indicator.

Although evidence can be found for the first three indicators, there is still no documentation for the fourth indicator—the security balance—which is extremely important. This indicator will only be verifiable once Afghanistan joins one of the security alliances of the region. Although significant inherent and political contradictions exist between Afghanistan and Eurasian countries, especially under Taliban rule, the Eurasian order has various motivations to incorporate Afghanistan into its system.

The most important motivations stem from Afghanistan’s geopolitical, geostrategic, and geoeconomic position. Eurasian countries—particularly Russia, as the region’s leading pole—would welcome Afghanistan’s alignment with their order. They hope that such a development would not only mitigate the security threat posed by Afghanistan in terms of extremism but also prevent other powers from using Afghanistan as an arena for another Great Game. The economic and transit opportunities available to these countries through Afghan geography further encourage them to accept Afghanistan into their system. Although the ideological domestic policies of the Taliban—such as the ban on girls’ education—are criticized by these states, the authoritarian and centralized nature of the Taliban government is in many ways similar to the systems governing most countries in the region.

Potential Implications

Of course, it is still too early to speak with certainty about this transition and only certain indicators support this hypothesis. However, since this move will be strategic, it will yield geopolitical and geoeconomic consequences for neighboring regions.

Pakistan, as a member of the South Asian order, is concerned about Afghanistan’s rapprochement with Eurasia; for if this transition materializes, Pakistan’s long-held ambitions—such as its “strategic depth” policy—will collapse. Moreover, if Afghanistan disengages from the South Asian order and joins Eurasia, the new geopolitical and geoeconomic shift will benefit India. For this reason, Pakistan will attempt to prevent such a development. It may even be argued that one of the fundamental factors behind the developments of the past few months between Afghanistan and Pakistan—which resulted in military clashes—was Pakistan’s concern over this shift.

In contrast to Pakistan, India will strongly support this Afghan move because it will weaken Afghanistan’s ties with Pakistan. Should this transition become definitive, Pakistan may resort to costly measures to halt it.

If Afghanistan’s transition from the South Asian to the Eurasian order is realized, certain geoeconomic changes must also be considered. Under such circumstances, Afghanistan will seek to reduce its dependence on Pakistan and establish alternative routes. In this scenario, the port of Chabahar will have a strong chance to facilitate access for Eurasian states and Afghanistan to open waters. Likewise, the eastern branch of the International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) —with India’s support—will flourish. It may also be said that the Trans-Afghan Railway project proposed by Kabul through the Kandahar Corridor aligns with this vision; because the railway through the Kabul Corridor leads toward Pakistan, whereas the Kandahar Corridor could potentially connect to Iran’s rail network and the port of Chabahar.

Conclusion

Part of Afghanistan’s challenges stem from its heavy dependence on the South Asian order, which has taken shape over the past decades. The ongoing rivalry between India and Pakistan has imposed heavy costs on Afghanistan, and one of the reasons for the collapse of the republican system was the competition between these two countries inside Afghanistan. To distance itself from this costly order, Afghanistan has the option of connecting to Eurasia —but it is a costly and time-consuming transition. Although certain indicators support this shift, they are not yet complete. - Given the profound consequences of this potential transition, greater attention is necessary. To this end, it is recommended that current trends be closely monitored:

- The visits of Afghan and Eurasian officials and the content of their discussions, including between trade delegations;

- The volume of Eurasian investment in Afghanistan compared to that of other countries;

- Progress in rail, road, and energy transit routes through northern Afghanistan;

- Security negotiations between the Taliban government and Eurasian states, particularly Russia;

- Moscow’s efforts to secure defense and military agreements with Kabul;

- Formal recognition of the Taliban government by Russia and Central Asian states.

News code:4180

Author : Javid Hoseini Researcher at the Institute for East Strategic Studies (IESS)

Source : East Studies